[No audio this week; RIP old headset. 🙁 ]

I had originally planned this for no other reason than the sake of novelty. I am, after all, not the only small-time Internet movie critic consistently cranking out reviews for the benefits of whomever takes the time to read my words. I have a Canadian counterpart (no, not my wife), who goes by the handle ‘Marter’ and can be found reviewing movies as often as he can at Box Office Boredom. Since we both toil in the somewhat dank Internet basement clubhouse that is the Escapist user forums, I thought it might be keen to collaborate on a review. He agreed, and for our work I selected Edward Zwick’s 2003 historical epic The Last Samurai.

The year is 1877. While the United States continues to recover from its civil war, the nation of Japan is undergoing sweeping social change. Resisting this change are the samurai, the warrior caste whose ancient traditions are threatened by the onset of a modern age. To assist in bringing these men and women to heel, Japan conscripts Captain Nathan Algren, a so-called expert at dealing with and relating to native cultures. In this case, it meant helping a tribe of Native Americans let their guard down long enough for his superior officer to ride in with their cavalry unit and kill everybody. Bitter, nihilistic and half in a bottle, Algren takes the job just for something to do, and ends up captured and isolated by the rebellion’s leader, Katsumoto, a learned man of both word and sword who may well be the last true samurai left in Japan.

So much for the synopsis. Our review of this film has been broken into five sections: Plot, Characters, Cinematography/Mise-en-scène, Actors and Fun Factor. Let’s get started with Marter’s take on…

Plot

Oh, and let’s not forget the random ninja attack. It was like director Edward Zwick thought “Hey, they might be getting boring. Let’s have a random action scene!” Sure, it was explained, but not very well, and then it’s never brought up again. I mean, it serves a function and it brings some of the characters together, but making it have some sort of relevance would have been much nicer.

The beginning scene also didn’t quite work for me. It showed us how far this soldier had fallen, but if he was willing to fall that far, more or less giving up hope in human life, why would he accept a lot of work just for some money. Opening this way shows his character doesn’t care too much about his life, or the money he can get, and makes me question why he’d take the $500 a month to teach people how to kill other people.

Most of the plot worked well, though. Despite the film lasting over 150 minutes long, I had no problem sitting through it because there was a lot to take in, and there was always something new happening. I wasn’t bored, and even if there wasn’t a random ninja attack, I don’t think I would have had a problem going over an hour without a real action scene. Watching the life of the samurai, like what I assume happened with Cruise’s character, was interesting to me. I was fine sitting there and simply observing.

Personally, it struck me a bit as Dances with Wolves in Japan. When I first saw the film it felt like a win/win. Dances with Wolves was a deeply affecting piece and I’m a sucker for the history, culture and fables of a land like Japan. However, in retrospect I can’t help but feel there’s been a little glossing over and touching up of some things in places when it comes to an actual portrayal of life during the Meiji era.

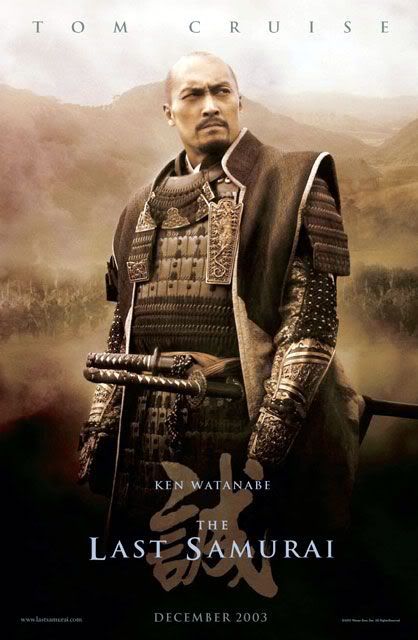

I feel what’s missing is the atmosphere of uncertainty. For the most part, Katsumoto (Watanabe) is absolutely sure his rebellion will ultimately serve the Emperor and strengthen his country, while his enemies are absolutely sure their modern way of life will prevail over the ‘barbarians’ who were once universally revered, respected and feared. In a time when nobody was sure what the future would hold, seeing things painted so starkly in black and white dilutes the emotional impact of the experience.

Still, Katsumoto’s desire to resist change for the good of his people’s heritage rings true and is enough to drive the plot outside of Algren’s growth as a human being. The time dilation that occurs can be a bit off-putting, as Marter mentioned, but the scope of the film and the way Zwick shoots it (more on that later) ensures we as the audience are aware of how sweeping the tale is in its scope. It makes a worthy attempt at being an affecting historical tragedy but never reaches the lofty heights of the Greeks or Shakespeare. The lack of moral ambiguity is probably the biggest Achilles heel this movie has plot wise, but it’s not enough to cripple it.

Honestly, I think the beard works for Cruise.

Characters

He develops though, mostly just as he switches sides from the government to being a samurai. So at least there’s that. Watanabe’s character doesn’t really develop at all. He’s the same at the beginning as he is at the end, with the only difference being that he finished his poem. Wow, that’s a lot of character development there. None of the secondary characters got either depth or development, although that didn’t bother me too much, as we didn’t need to make the film more cumbersome than it already is.

While Katsumoto doesn’t really have an arc the way Algren does, that doesn’t necessarily mean the character’s dull. Is an old tiger dull just because it’s old? We see Katsumoto knowing what he does may end his life at any time, and his willingness to face death, at least his own. The deaths of others, however, have more of an effect on him. One of the film’s best scenes comes when his carefully-crafted mask of tranquility is shattered by someone getting fatally wounded. I won’t say who or when, but trust me that it’s an example of a great deal of emotion and depth being conveyed without a single word.

The one-dimensionality of the other characters does indeed keep burdens to a minimum as the story progresses and ties in to that lack of moral ambiguity I mentioned. There are no real surprises when it comes to the allegiances or motivations of people, making the overall story feel like a duet between Algren and Katsumoto with everybody else playing instruments in the backing band. But at least those two are decent characters, even if Algren seems a bit inconsistent at times. He also, thank the Maker, never becomes a “magical white person”, solving all of the problems of his poor minority friends simply by being there or making a speech. During the final battle he does play a role but never becomes a major factor, and in the aftermath maintains his place as an observer and narrator rather than a firebrand or symbol. He drives home the point of Katsumoto’s rebellion, but in the end seems somewhat superfluous to the actual historical events. To be honest, I like that.

Better that than him rallying Japan to remember its traditions the way a white person is sometimes shown as making a black person a better football player or being responsible for a civil rights movement.

Cinematography/Mise-en-scène

The battle scenes, unfortunately, might have been the low points of the film. It’s not that they’re not well-made, because I think they were, but because they just didn’t particularly fit with the rest of the film, which is a slow-paced drama. The first scene, where the military is slaughtered, is not particularly interesting because we’ve yet to have enough time to care about anyone involved, especially in regards to the enemy. But luckily, it’s short and then it takes a while for another battle to be fought.

I must again respectfully disagree, with regards to the first battle. While we really don’t care much about anybody outside of Algren, and even so only in passing at that point, the sight of the samurai in full armor riding hard out of the mist gives them an eerieness that works very well, in my opinion. It’s obvious to me why the newly-crafted Japanese army breaks at the sight of them. As is explained to Algren, most of those men grew up hearing tales of the samurai and being in awe of their power and honor. And then, like specters of the past, they’re coming directly at you, screaming like banshees and carrying deadly weapons. It’s a psychological tactic that works beautifully and speaks to Katsumoto’s craftiness in battle strategy, not to mention making for a great shot.

Going back to a previous point, though, the ninja attack is probably the “low point” of the film for me. With the exception of two moments I can think of, nothing particularly interesting happens either story-wise or in terms of shot composition. As Marter mentioned, it’s pretty much just Zwick saying, “Have some ninjas, guys!” Sure, sending assassins after Katsumoto makes sense, but what is this, G.I. Joe?

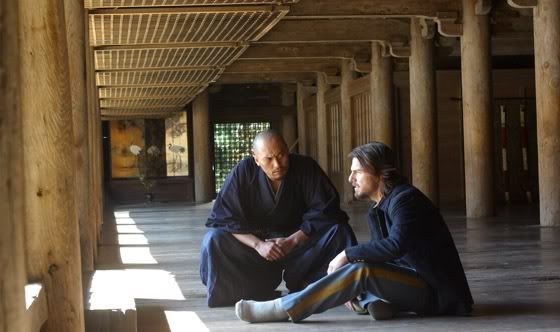

Pretty much any scene with these two in it is a good one.

Actors

I agree completely. Tom Cruise all but disappears into his role and it makes the rest of the film better. There are a couple moments early on when he might be overdoing it a bit with the way his character is ‘tortured’, but looking past that we find a performance that conveys Algren’s arc in an earnest, very human manner. He truly brought his A game, which is a good thing because Watanabe shows he is fully capable of blowing less talented actors completely out of the water. The aforementioned death of another character is all but perfect in its presentation and Watanabe absolutely nails it. As I said, this really comes down to a duet between these two characters, and the way the actors play it makes their conversations the highlights of the film.

Fun Factor

In spite of its historical inconsistencies and a few moments that push the melodrama almost to the point of absurdity, The Last Samurai never feels less than sincere in its sentiments and presentation. It may not always work as intended and you may have trouble shaking the feeling that Zwick is trying really hard to remake Glory, but historical war stories are his bailiwick and this one isn’t bad at all. Between the lush cinematography, the interesting historical aspects of the story and the powerful performances of the two leads, it’s safe to say both Marter and I recommend The Last Samurai.

However, when you look up what actually happened in Japan during the Meiji Restoration, from the actual number of samurai to the way the Japanese were using their Western ‘experts’, you may get a little bit angry at the aforementioned inconsistencies. I don’t think this necessarily detracts from the performances or cinematography, but nevertheless, consider yourselves warned.

Josh Loomis can’t always make it to the local megaplex, and thus must turn to alternative forms of cinematic entertainment. There might not be overpriced soda pop & over-buttered popcorn, and it’s unclear if this week’s film came in the mail or was delivered via the dark & mysterious tubes of the Internet. Only one thing is certain… IT CAME FROM NETFLIX.